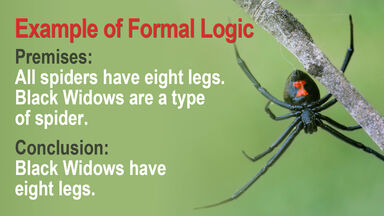

It is, in fact, a common point of Jevons, Sigwart and Wundt that the universal is not really a conclusion inferred from given particulars, but a hypothetical major premise from which given particulars are inferred, and that this major contains presuppositions of causation not contained in the particulars.

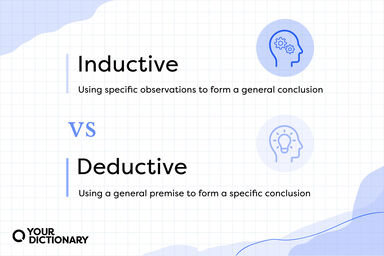

In the same way, to infer a machine from hearing the regular tick of a clock, to infer a player from finding a pack of cards arranged in suits, to infer a human origin of stone implements, and all such inferences from patent effects to latent causes, though they appear to Jevons to be typical inductions, are really deductions which, besides the minor premise stating the particular effects, require a major premise discovered by a previous induction and stating the general kind of effects of a general kind of cause.

As we have seen, Jevons, Sigwart and Wundt all think that induction contains a belief in causation, in a cause, or ground, which is not present in the particular facts of experience, but is contributed by a hypothesis added as a major premise to the particulars in order to explain them by the cause or ground.

But whether Kant be right or wrong, Wundt and his school are decidedly wrong in supposing " supplementary notions which are not contained in experience itself, but are gained by a process of logical treatment of this experience "; as if our behalf in causality could be neither a posteriori nor a priori, but beyond experience wake up in a hypothetical major premise of induction.

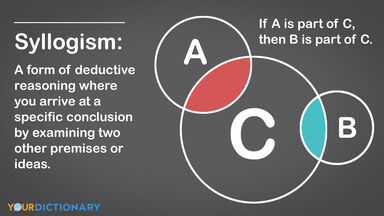

Bradley seems to suppose that the major premise of a syllogism must be explicit, or else is nothing at all.