Even if you don’t know Morse code, you’ve probably heard of SOS, and maybe even know what it looks or sounds like. If you’ve always heard that SOS stands for “save our ship,” the real SOS meaning may surprise you. Surprise! It doesn’t stand for anything! Still, that doesn’t make those beeps and boops any less important or useful.

What Does SOS Stand For?

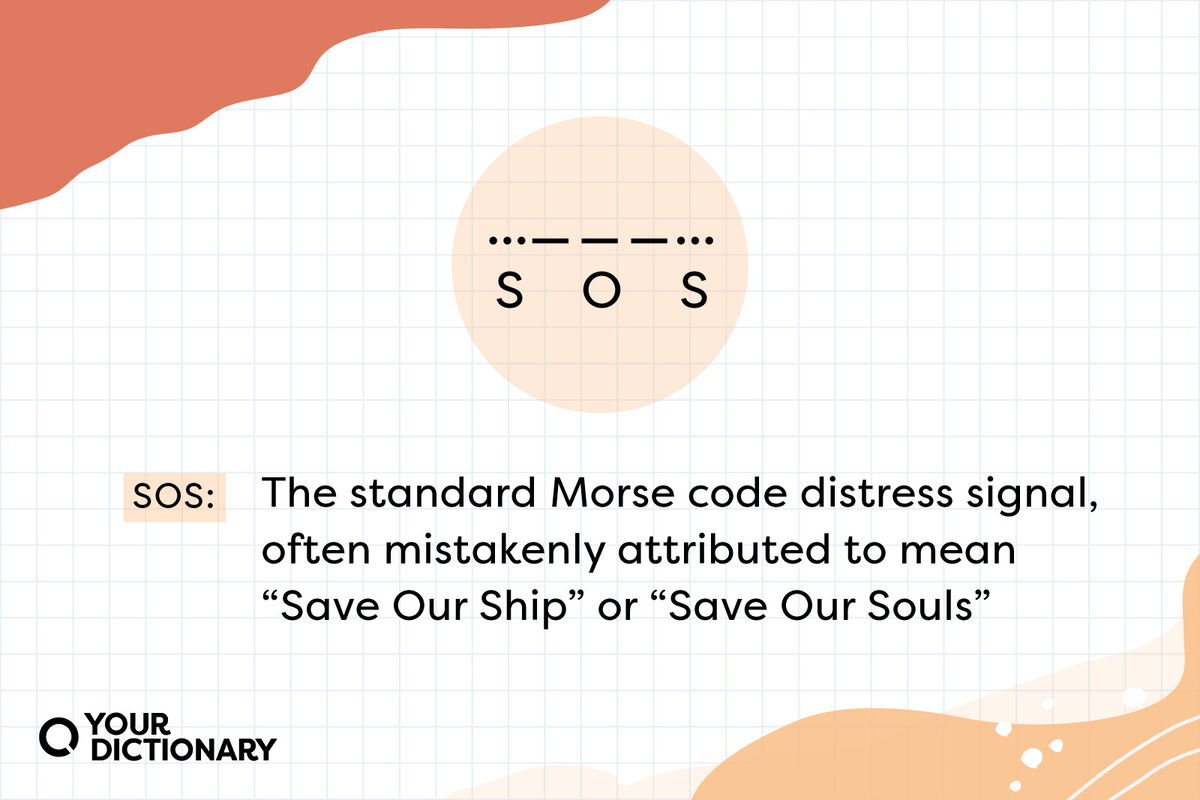

In Morse code, SOS is made up of three dots, three dashes, and three more dots: …---...

Because it’s made up of three letters, it’s natural to assume SOS is an acronym. However, it was never meant to stand for anything. The Marconi Yearbook of Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony, published in 1918, gives an explanation of the meaning, or lack of meaning, behind the letter choices.

This signal [SOS] was adopted simply on account of its easy radiation and its unmistakable character. There is no special significance in the letters themselves...

SOS was chosen as a distress signal because it was easy to understand in Morse code and not likely to be confused with other signals.

It also has the added benefit of being a palindrome, a series of letters that read the same backward and forward.

SOS also looks the same upside down as it does right side up, making it an ideal series of letters to view from the air if written on a beach or in the snow.

Reverse Acronyms for SOS

Although SOS doesn’t actually stand for anything, there have been many reverse acronyms proposed for it. The two most common are:

- Save Our Ship

- Save Our Souls

In reality, SOS does not mean either of these things. It’s simply a series of attention-grabbing and easily understandable letters that create a universal code.

What Is Morse Code?

Developed by Samuel Morse, Morse code is a form of long distance communication depicted in sequences of different durations. Dots (.) are short, while dashes (-) are long. This can be transmitted through sound or visually through lights.

History of SOS and Morse Code Distress Signals

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Morse code was the only way ships could communicate with one another while at sea. Wireless operators could send messages from one ship to another using the telegraph and Morse code, and there were shorthand ways to communicate important messages quickly.

CQD: A Predecessor to SOS

Prior to the adoption of SOS, regions often had their own preferred distress signal. For many countries, particularly in Great Britain, the preferred signal was CQD: -.-. --.- -..

Some people mistakenly believe that CQD stands for “Come Quick, Danger,” but much like SOS, CQD doesn’t actually stand for anything and is just a general call for all stations.

When asked whether CQD stood for anything, Harold Bride, a wireless operator who survived the sinking of the Titanic, reported that it was “merely a code call” and not an acronym.

SOS Adopted in 1906

In 1906, the International Radio Telegraphic Convention in Berlin agreed on a new official distress signal: SOS.

Ships in distress shall use the following signal: …---... repeated at brief intervals… It seems necessary to specify that indications concerning a case of distress should be given by means of conventional signals in order that they may be understood by all stations.

However, many telegraph operators refused to adopt the new universal signal and stuck with their own signals for several years after SOS was adopted. That would all change with the sinking of the Titanic.

Distress Call of the Titanic

In 1912, the Titanic struck an iceberg during a transatlantic journey. The ship sank rapidly in frigid waters, and the loss of life and dramatic nature of the disaster revolutionized the way people thought about the SOS distress signal.

The telegraph operators on board the Titanic sent a mix of SOS and CQD, joking that this might be their last chance to try the new signal of SOS. The messages became confusing in the panic. Help did not come in time, and after the disaster, SOS became the standard international distress call.

Modern Use of SOS

Because of the advancement in modern telecommunications, SOS and Morse code are falling into disuse. In 2007, the Federal Communications Commission eliminated the requirement that radio operators must know Morse code. The Navy still uses it, but it is not their primary method of signaling distress anymore.