It may not seem like possessive adjectives are as important as regular adjectives. But when it comes to the difference between “my chocolate chip cookie” and “your chocolate chip cookie,” you definitely want to use the correct possessive adjective. (Now give me back my cookie.)

What Are Possessive Adjectives?

Possessive adjectives are little words in front of nouns that show who owns that noun. Like other adjectives, they modify the noun that comes after them.

- Let go of my purse! (my modifies purse)

- Is this your dog? (your modifies dog)

- Law school has always been her dream. (her modifies dream)

- That’s not our business. (our modifies business)

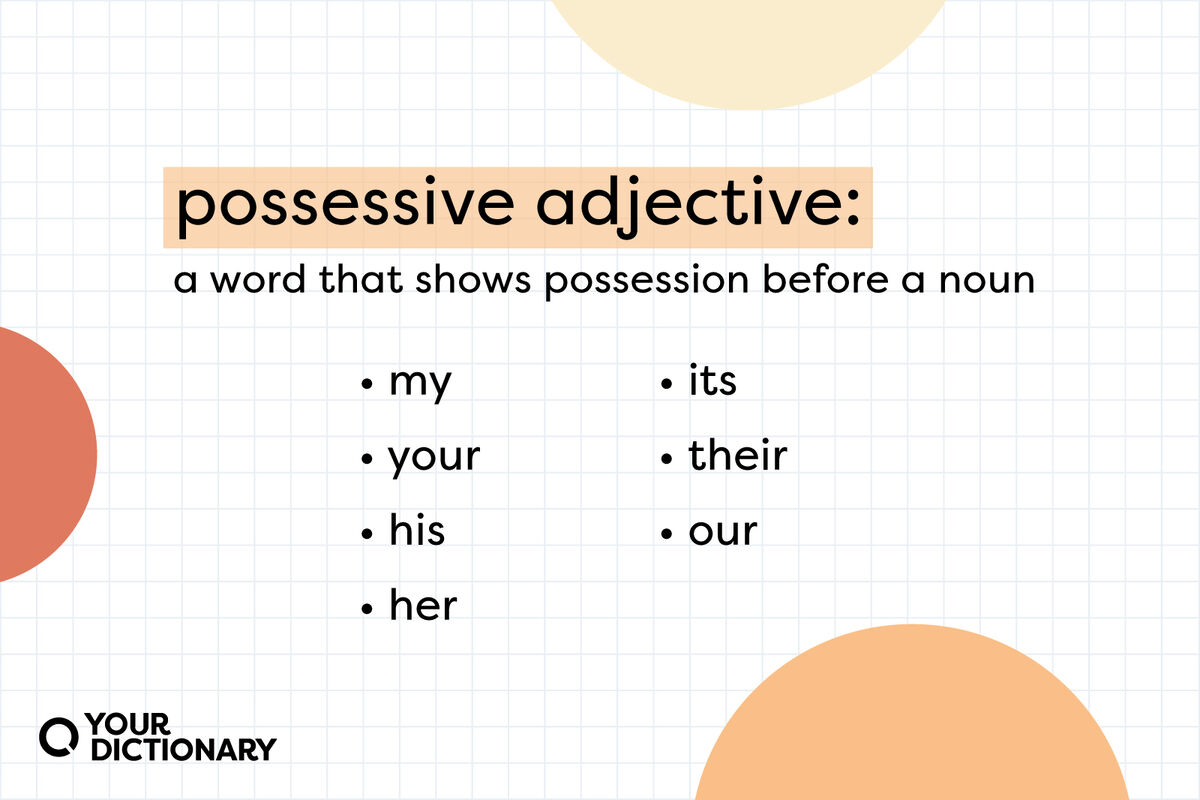

List of Possessive Adjectives

The most common possessive adjectives are:

- my

- your

- his

- her

- its

- their

- our

- whose

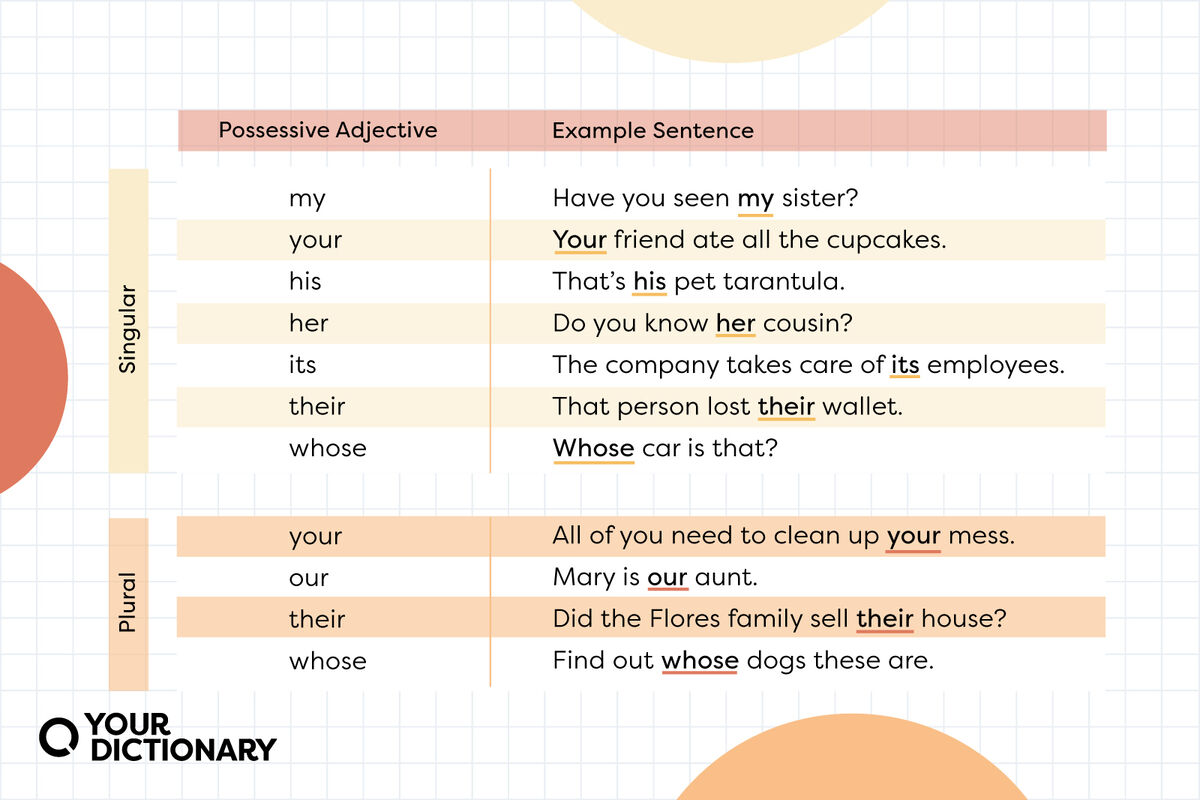

Unlike other adjectives, possessive adjectives change based on the sentence. They can be singular or plural, depending on their antecedents (the noun they replace).

Your, their, and whose can be singular or plural based on the sentence they’re in. We use whose before nouns when we don’t know the owner. It can function in questions (Whose iguana is this?) and adjective clauses (I don’t know whose iguana that is.)

How To Use Possessive Adjectives in a Sentence

Possessive adjectives are odd parts of speech. They sort of function like pronouns, and they sort of function like adjectives — but they’re a little bit different from each one.

Replacing Possessive Nouns

Possessive adjectives (also known as possessive determiners) have a unique function in a sentence. Not only do they modify nouns, but they also replace possessive nouns that come before those nouns to keep your writing from sounding repetitive.

(Note: Only third-person pronouns — his, her, its, their, our — replace the nouns, since my and your always refer to me and you.)

- Have you seen Elliot’s homework?

- Have you seen his homework?

- Please examine the bird’s wings for any injuries.

- Please examine its wings for any injuries.

- That’s not this class’s graduation cake.

- That’s not our graduation cake.

Possessive Adjective Agreement

Possessive adjectives follow pronoun agreement rules. They must agree with the antecedent, meaning that singular possessive nouns (Mike’s, Kari’s, the cat’s) must match the possessive adjectives (his, her, its).

Usually, the antecedent is clear from a previous sentence or other context clues.

- Mike loves going to concerts. His favorite concert was the Backstreet Boys in 2000.

- Kari has always wanted to travel to Paris. It’s her biggest dream.

- The cat screeched when I accidentally stepped on its tail.

- You and your friends should pay for your own trip.

- John and Eric asked if we could get their mail.

However, possessive adjectives don’t need to agree with the nouns they possess. In the last example above, the plural possessive adjective their agrees with the compound subject John and Eric, not the singular noun mail.

Possessive Adjectives vs. Possessive Pronouns

Many writers believe that my, your, his, her, its, their, and our are actually possessive pronouns.

While possessive adjectives may replace possessive nouns in a sentence, they are functioning as adjectives to modify the noun. Possessive pronouns (mine, yours, hers, his, its, theirs, ours) function as nouns in a sentence.

- That’s not the Smiths’ truck.

- Possessive adjective: That’s not their truck. (their replaces the Smith’s and modifies truck)

- Possessive pronoun: That’s not theirs. (theirs replaces the Smith’s truck)

- Is that Ella’s new house?

- Possessive adjective: Is that her new house? (her replaces Ella’s and modifies new house)

- Possessive pronoun: Is that house hers? (hers replaces her new house)

Notice that in these examples, possessive adjectives come before the nouns they own, while possessive pronouns come after the nouns they own (Is that house hers?) or replace them completely (Is that hers?)

Put Possessive Adjectives First (and Get Them Right)

Now that you know how to use possessive adjectives, it’s time to get them straight. Do you know the difference between you’re and your? What about whose vs. who’s — or the always-confusing it’s and its?