You’ve already written a basic essay of some kind, so you’ve already performed a bit of analysis. Really, you already have all the tools and know-how to tackle a critical analysis essay. Unlike other essays, critical analysis essays ask that you go a little deeper into other people’s ideas to build your own responses to art, media, and the world at large. Simple, right?

What Is a Critical Analysis Essay?

Okay, there’s admittedly maybe a little more to it than just that. A critical analysis essay is a form of writing that asks you to:

- Analyze a subject, which may include a historical document, a scientific theory, or a piece of art or media (books, poems, movies, even other essays)

- Determine what the author of that piece is trying to say

- Respond with ideas of your own, backed up with evidence from other texts or media

Critical analysis branches out into things like literary criticism, genre studies, and editorial journalism. If you want to think about it on a smaller scale: Have you read a tweet thread or blog post and thought, “Hey, I have a differing opinion!” or “I agree with this”? Have you then responded to that post or thread with your own opinion? Congrats! You did a little critical analysis!

General Structure and Format of a Critical Analysis Essay

You’ll find some variations in form and structure with the critical analysis essay. As you get more comfortable with it, you can absolutely change things around and get creative. Otherwise, don’t overthink the format too much.

Your typical critical analysis essay is made up of:

- An introduction paragraph, including your opinion about the piece you're analyzing

- A paragraph (potentially more) summarizing the thing that you’re analyzing

- Several paragraphs detailing:

- the actual analysis of the piece, which will usually include your opinion about that piece

- an evaluation of the author’s success in achieving their intended goal

- a larger idea or argument within the text that you can elaborate on

- A concluding paragraph that sums up your analysis and relates it to your audience

Sometimes, the summary paragraph is shortened and folded into the introduction.

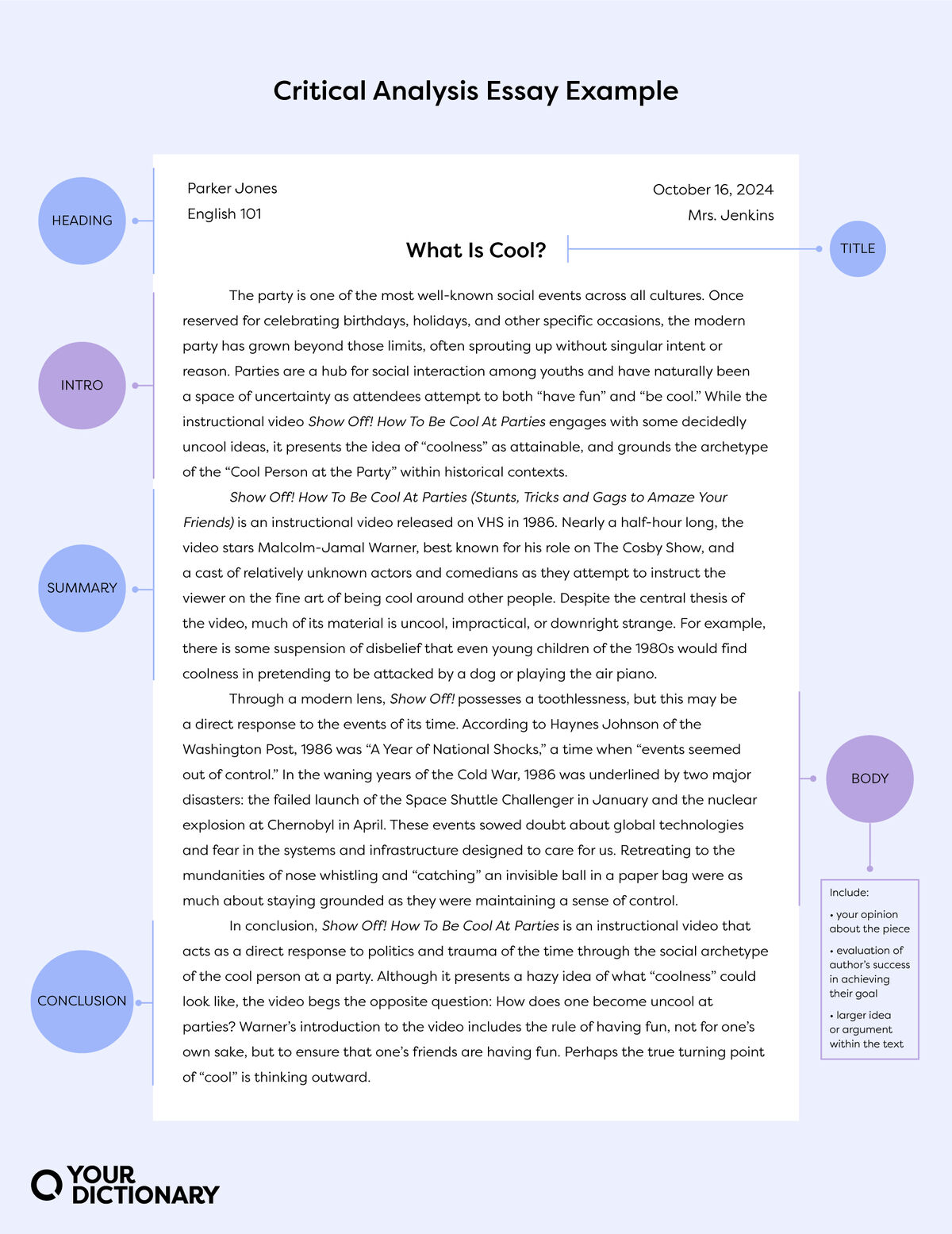

Critical Analysis Essay Example

Seeing is believing (and understanding). We can’t help you with your actual critical analyzing, but we can at least give you an example of a critical analysis essay to show you how it might look. Note that we’re not in the business of giving away free essays, and that this is purely to help you see a (fairly incomplete) critical analysis essay in the works.

The Introduction Paragraph

With your introduction, you want to hook readers, broadly introduce the ideas that you’ll talk about, and give readers a reason to read the essay in its entirety. The most important part of the intro is the thesis, which states your central argument. In its most general sense, that includes what you think about the piece and the larger idea you think it might present.

The party is one of the most well-known social events across all cultures. Once reserved for celebrating birthdays, holidays, and other specific occasions, the modern party has grown beyond those limits, often sprouting up without singular intent or reason. Parties are a hub for social interaction among youths and have naturally been a space of uncertainty as attendees attempt to both “have fun” and “be cool.” While the instructional video Show Off! How To Be Cool At Parties engages with some decidedly uncool ideas, it presents the idea of “coolness” as attainable, and grounds the archetype of the “Cool Person at the Party” within historical contexts.

The Summary Paragraph(s)

Following the introduction, you have your summary of the piece or object that you are critically analyzing. Depending on the work and the requirements of the assignment, this might expand to more than one paragraph. Some classes may also do without it completely (your professor, who has read The Great Gatsby, probably doesn’t need you and the 15 other students in the class to summarize it.)

The summary generally shouldn’t be an in-depth, beat-by-beat retelling of the thing that you’re analyzing. You want to give enough details that your reader knows what you’re talking about without having to necessarily read or watch what you’re analyzing.

Show Off! How To Be Cool At Parties (Stunts, Tricks and Gags to Amaze Your Friends) is an instructional video released on VHS in 1986. Nearly a half-hour long, the video stars Malcolm-Jamal Warner, best known for his role on The Cosby Show, and a cast of relatively unknown actors and comedians as they attempt to instruct the viewer on the fine art of being cool around other people. Despite the central thesis of the video, much of its material is uncool, impractical, or downright strange. For example, there is some suspension of disbelief that even young children of the 1980s would find coolness in pretending to be attacked by a dog or playing the air piano.

The Analysis Paragraphs

This is where you’ll really get into your critical analysis. Along with presenting your own opinions and engaging with the chosen text, you should draw evidence from other authoritative sources, which can support your argument and present new ideas that you can build off of.

Through a modern lens, Show Off! possesses a toothlessness, but this may be a direct response to the events of its time. According to Haynes Johnson of the Washington Post, 1986 was “A Year of National Shocks,” a time when “events seemed out of control.” In the waning years of the Cold War, 1986 was underlined by two major disasters: the failed launch of the Space Shuttle Challenger in January and the nuclear explosion at Chernobyl in April. These events sowed doubt about global technologies and fear in the systems and infrastructure designed to care for us. Retreating to the mundanities of nose whistling and “catching” an invisible ball in a paper bag were as much about staying grounded as they were maintaining a sense of control.

Much of Show Off! is built on the archetype of the “Cool Person at the Party.” This archetype is largely left to the imagination of the viewer as funny, dexterous, readily armed with props and parlor tricks, and attainable by anyone. In the essay “Myth and Archetype in Science Fiction,” author Ursula K. Le Guin states that “nobody can invent an archetype by taking thought, any more than he can invent a new organ in his body.” She goes on to say that myth and archetypes are a means of communication and that “alienation isn’t the final human condition, since there is a vast human ground on which we can meet, not only rationally, but aesthetically, intuitively, emotionally.” Given global uncertainties, the process of becoming a cool person at a party is equivalent to reaching for connection, familiarity, and communication.

The Concluding Paragraph

Your conclusion should restate the thesis, act as a general wrap-up for your essay, and consider questions or ideas beyond what you discussed in the body paragraphs. A critical analysis essay can also end with a call to action about engaging with the analyzed piece, but this isn’t a requirement.

In conclusion, Show Off! How To Be Cool At Parties is an instructional video that acts as a direct response to politics and trauma of the time through the social archetype of the cool person at a party. Although it presents a hazy idea of what “coolness” could look like, the video begs the opposite question: How does one become uncool at parties? Warner’s introduction to the video includes the rule of having fun, not for one’s own sake, but to ensure that one’s friends are having fun. Perhaps the true turning point of “cool” is thinking outward.

Let’s Get Critical!

Critical analysis essays can be difficult for people of all education levels. Learning to think (and write) critically comes with practice, so don’t be afraid to play around with your language. Discover new ways to engage with what you read, watch, experience, or listen to using our helpful tips for writing a critical analysis essay.