Despite what you’ll see from certain chronically online people, a good argument doesn’t come from figurative yelling and making up facts. An argumentative essay is a great tool for teaching you how to present effective, meaningful arguments while still using your own voice and writing style (without ever even touching that caps lock key). Developing a good argument and presenting it in writing isn’t easy, but a little thought, preparation, and helpful tips can have you debating with the best of them.

Plot Your Argument With an Essay Outline

It doesn’t matter how many essays you’ve written or how sure you are of your writing. You should always start with an outline. It could be as basic or as in-depth as you want, but an outline helps you get the blueprint of your entire essay onto paper while helping you flesh out your inklings into ideas.

In its simplest form, an argumentative essay will include:

- Introduction: A paragraph that includes a hook to draw the reader in, some ideas to introduce your argument, and the thesis statement that presents the actual claim you’ll be discussing in your essay

- Body paragraphs: The main paragraphs of the essay that will dissect your argument, look at evidence to support that argument, and examine potential counterarguments and rebuttals

- Conclusion: A paragraph that restates your initial argument and considers larger questions that you might not have directly addressed in your essay

Remember that this is just an outline. Think of it as a pre-draft. You can diverge from your outline as you get into the actual essay writing, but it gives you a place to start.

Understand the Length of Your Argumentative Essay

The good and bad news about argumentative essays: There isn’t a set length. You’ll mostly have to rely on what your instructor or the essay guidelines state. That can range from a fairly basic five-paragraph essay to a multi-page dissertation.

In most circumstances, your argumentative essay will clock in at about three to five pages, which is about 1,000 to 1,500 words. If you’re ever in doubt, check the syllabus or ask your instructor directly.

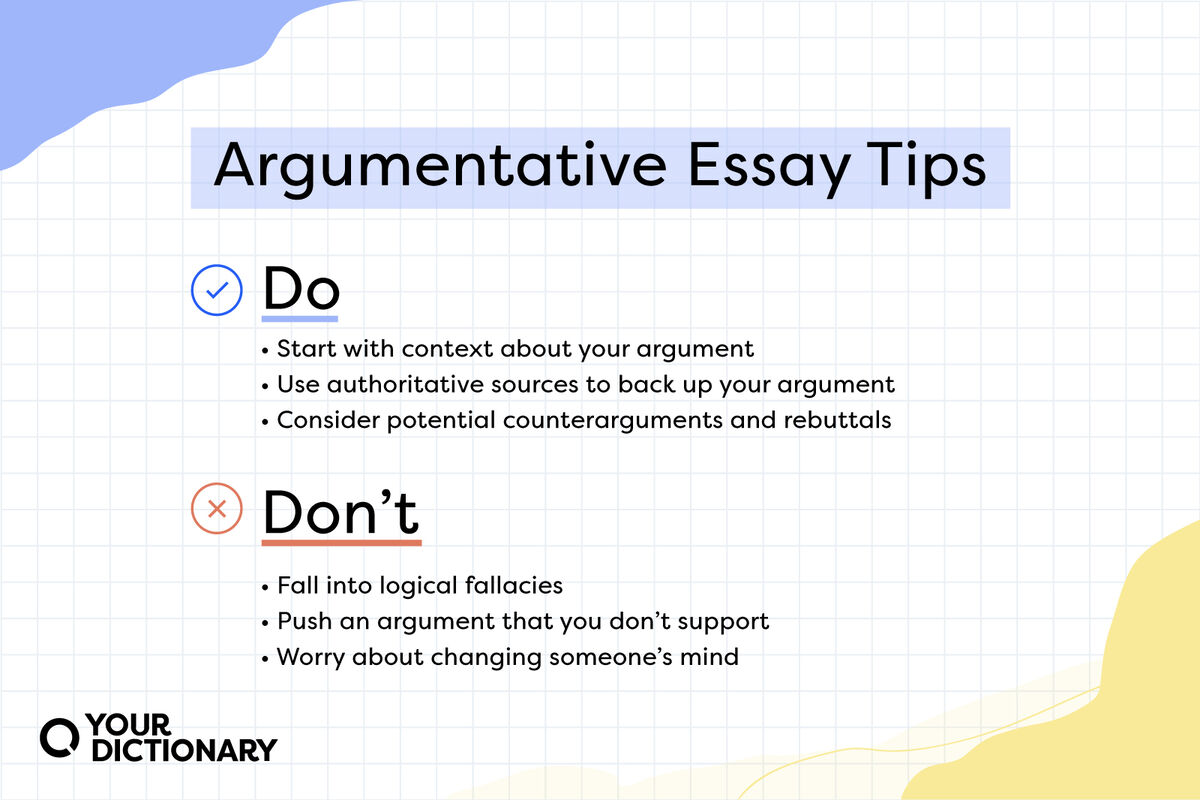

Begin Your Essay With Context

Many people have trouble beginning their argumentative essays. You might be ready and raring to dive deep into your argument, but getting immediately into your argument can be confusing. Use your introduction and first body paragraph to really set the table and provide context behind the argument.

- What is your exact stance?

- Why is the topic in question something worth arguing about?

- Why do you personally feel strongly about the topic?

Watch Out for Logical Fallacies

It is really easy for any arguer to fall into the logical fallacy trap. A logical fallacy is an error in logic that can be easily disproved with reasoning. This usually manifests as you drawing conclusions from nowhere, which makes for a thin essay and a completely undermined argument.

Logical fallacies come in many forms, from straw men to red herrings. It’s a good idea to recognize these logical fallacies to avoid them in your writing and spot them in other arguments.

Use Authoritative Sources and Good Evidence

One good way to avoid fallacies is to use authoritative sources the right way. You might know your way around your topic of choice, but instructors (and readers) need evidence from other sources to back up your arguments. Using evidence from other sources can also add a little extra spice to your argument. How do you find “good” sources?

- Use texts that have already been discussed in class.

- Check notable periodicals, including newspapers, magazines, and scholarly articles.

- Ask your local librarian.

- Search online (stick with journalistic sources: .gov sites, JSTOR, PubMed).

- Look at sources within sources.

Always double-check any information you find with information from a separate source. If you need extra help finding credible sources, talk to your instructor. Most instructors will at least give you a nudge in the right direction.

Find an Argument That You’re Invested In

It can be really hard to argue something that you don’t really care about or believe in. You could do all the studying and research you want, but if you’re not invested in your argument or can’t stand by it, your writing will reflect that.

If you can’t change the overarching argumentative essay topic, try to come at your argument from a different angle.

- Think about it in terms you might understand better to get you closer to what you care about.

- Consider how the topic relates to other topics or themes in history, politics, psychology, and other subjects. Nothing exists in a bubble!

- Look at arguments that you agree with. Is there some small nuance to that argument that you would change or expand on?

Consider Any Potential Counterarguments and Rebuttals

An inherent thing with any argument: There’s always going to be at least one opposing view. While some people worry that even bringing up a potential counterargument or rebuttal will detract from their points, acknowledging any counterarguments will strengthen your own argument, make you more persuasive, and help you understand your own views.

You don’t have to go into immense detail with the counterargument, unless that helps with your own research. Using although and however statements is a great way to respectfully acknowledge the opposing view while setting up your own argument.

Although some people believe that tacos are merely a novelty food, centuries of culinary tradition suggest that the taco is one of the most important foods in global culture.

Don’t Worry About Changing Someone’s Mind

This might seem counterintuitive, but don’t worry about changing someone’s mind. People can be stubborn about their thoughts and convictions. No matter how incredible your essay is, stuffed with an unreal amount of hard evidence, a reader may not budge an inch on their opposing viewpoint, and that’s okay. That doesn’t mean you should write an indifferent, bland, non-persuasive essay, but it does mean that you should understand the aim of your argumentative essay.

As with any piece of writing, the argumentative essay is a transfer of information. Even if someone doesn’t change their mind, what nugget of information do you want them to take away? You won’t change someone’s mind about cats, but maybe you can teach them about the history of cats in parallel to humans and agriculture. That’s just a cool fact to learn.